Readers of Anthony Foreman’s publication “Lidgate -Two Thousand Years of a Suffolk Village” will know that in the 1980s a child playing near Cowlinge Corner in Lidgate found a skull and accompanying bones in the earth.

Police were called out and bones were taken away – but as Anthony Foreman writes “…to date no solution of the mystery has been found”.

There is a complicated story attached to the Lidgate bones, with evidence of more than one skeleton found. We don’t know whether the bones were of an adult, a child or both; we do know that the police removed at least one skeleton, but it’s present whereabouts are unknown.

The Lidgate Archaeology Group, wanting to find out more, asked me to research the skeletons. I had a number of threads to follow up – the Newmarket Local History Society, Moyse’s Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds, the Suffolk Local Records Office, the local newspaper, police records and, intriguingly, Romany lore.

Due to their presentation in the earth at the time of discovery there was conjecture from some that the bones may have been placed there in an upright position.

However, upright burials are a very rare phenomenon in the archaeological world. There is one well documented case of an upright burial, dated to c 4900 BC, discovered in 2012 in a Mesolithic cemetery site first excavated in 1962, in Grosse Fredenwalde, Brandenburg, N E Germany. There are possibly 4 similar burials known in Karelia, Russia, but in all cases there is no firm indication as to why the burial presented in this way.

I found references to two other supposed upright burials – the first, according to his biographers, was of the poet and playwright Ben Jonson (1572 – 1637), apparently interred in an upright position in Poets Corner, Westminster Abbey, possibly as a result of his extreme poverty at the time of his death. He was reputed to have said “…two feet by two feet will do for all I want”, and also to have begged “…just 18 inches of square ground” in the Abbey from King Charles 1st – and consequently to have received an upright grave to fit the requested space. The second reference was to the18th/19th century Suffolk archaeologist and geologist Edmund Tyrell Artis, who was said to have asked to be buried upright in Castor churchyard, supposedly so that he could “view” his excavations at the Roman town of Durobrivae nearby. This latter is mentioned as a local legend in “Peterborough Folklore” by Francis Young.

Some members of the Lidgate Archaeology Group, remembered hearing the phrase “Bury me standing for I have spent my whole life on my knees” and thought it might be a Romany saying. Could the skeletons have been a Romany burial – and was there a Romany tradition of upright burial? I consulted a number of books on Romany history and found no mention of upright burial as a Romany custom.

The only confirmed Romany custom I found related to death was the tradition of burning both the caravan and possessions of the deceased after their burial.

I posted an online enquiry on “Romany Routes” (the Romany Family History Society) and received some interesting replies. The phrase “Bury me standing for I have been on my knees all my life” was known by members of “Romany Routes”, and confirmed that it had been used as the title of a book by Isabel Fonseca about the Eastern European Roma. It was, however, emphatically stated by members of the society that it was not a Romany burial custom, and probably not an expression used by the British Romany community. Interestingly, one respondent commented :

“My Nana used to say that all the time. In fact we still say it in our family. I had always understood it to be just a turn of phrase. So for example, say she’d just got the kitchen spick and span, and someone left a dirty plate on the table, she’d call out ‘Bury me standing then, I’ve been on my knees all my life, so that’s me’. Although we are a British family, Nana spent some years in Hungary as a young bride, and mixed with European travellers, so she might have picked it up there. I never thought it was meant to be taken literally”.

So from this I concluded that there was no Romany tradition of upright burial – but that there is a tradition of Romany wit, alluding to the trials of existence in the saying “Bury me standing for I’ve been on my knees all my life”.

I discovered a mention of the Lidgate bones in “A Survey of Suffolk Parish History – West Suffolk” published by Suffolk County Council in 1990. This was researched by Wendy Goult who mentions in the section on Lidgate “Ancient child’s skull found in Lidgate Brook in 1986”. I contacted Wendy Goult who was able to confirm the date.

I checked the Suffolk Police Disclosure Logs online, where, in the section “Operational Policing”, they listed responses to Freedom of Information Requests. In response to requests in 2016/17 asking about unidentified and unsolved finds of human remains the police listed all the occurrences of finds of such remains as far back as1961. I checked through these and could not find any mention of the Lidgate bones. There were numerous mentions of unidentified bones and skeletons – but none found in Lidgate.

In search of the local paper’s report of the Lidgate finds I emailed the Newmarket Journal, asking if they maintained a set of archives dating back as far as the 1980s but received no useful information. I checked the Suffolk Records Office archival holdings online but could find no reference to the Lidgate bones there.

Newmarket Historical Society were very helpful in their response. They had no definite information but suggested contacts at Moyse’s Hall Museum in Bury St. Edmunds. I emailed the contacts but again they had no knowledge of the bones.

So, having undertaken the above initial, and inconclusive research, it may now be useful to ask the following question “What might be the real significance of the skeletons, and what can their discovery alert us to, particularly when we think about the landscape features in which they were found”.

We know that the find spot for the skeletons at Cowlinge Corner is near to Lidgate Castle – a protected site, dating to the 12th century and listed by Historic England (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1006024).

In 2018 the Lidgate Archaeology Group contacted Historic England asking, as a result of new data, for a wider area surrounding the castle to be included in an extended protected area. After visits, discussions, presentations of historical and archaeological evidence, Historic England agreed to extend the area of protection from the immediate environs of the castle and fortifications to include the medieval burgage plots (house sites) lower down the slope from the castle, towards the Bailey Pond, thus protecting a larger area for the future.

Research commissioned at that time by the Lidgate Archaeology Group resulted in geophysical surveying, LIDAR (Laser Imaging Detection and Ranging) imaging and borehole sampling, and analysis of the meadow areas immediately south of the newly extended Historic England protected area. This research produced two reports: John Rainer’s “Lidgate Castle, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk. Report on Geophysical Survey, September 2018” and Steve Boreham’s “LIDAR and borehole investigations at Lidgate, Suffolk” 2019.

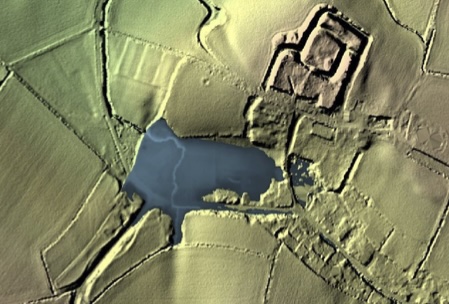

Analysis of the LIDAR image of the castle site (the castle with it’s surrounding deep ditches can be seen top right in the illustration), and of the area below it, together with borehole sampling and related investigations, lead to speculation that there may have been a much larger area of water – possibly a mere (as at Framlingham Castle) – extending to the west of the current Bailey Pond and onwards past Cowlinge Corner. The possible extent is shown in blue in John Rainer’s illustration using the LIDAR image:

The skeletons were found within this area of possible marsh or mere, so what can this context tell us about them, and what are the facts that we can draw on to approach a more realistic appraisal of their discovery?

We have recorded facts from the Suffolk Historic Environment Record for Lidgate where we see described two undated human skeletons seen in the river bank:

- Suffolk Historic Environment Record

- SHER Number: LDG 035

- Name: Two undated Human Skeletons

- Type of Record: Monument

- Grid Reference: TL 7185 5796

- Parish: LIDGATE, ST EDMUNDSBURY, SUFFOLK

Summary

Two undated skeletons, seen in the river bank, apparently stood upright, at least one was removed by the police, it is uncertain if the second one was.

Monument Types

INHUMATION (Unknown date)

Designated Status: none recorded

Description

Two undated skeletons, seen in the river bank, apparently stood upright, at least one was removed by the police, it is uncertain if the second one was.

Sources and Further Reading

—SSF59184 – Verbal communication: Wreathall, D.. 2019.

Associated Finds

FSF49186 – HUMAN REMAINS (Undated)

Date Last Edited: Jun 11 2019 3:38PM

I believe that while upright burials and Romany customs might be alluring in their somewhat exotic nature, the skeletons may have a different, but no less interesting story to tell us, and to that end I wrote the following formal report:

“The location of the skeletons is of interest, as it lies within the area of the suggested pond or mere extending to the west of the existing Bailey Pond, potentially forming part of “a wholesale reorganisation of the landscape and drainage around Lidgate village following the Norman conquest” (Steve Boreham “Lidar and borehole investigations at Lidgate, Suffolk” 2019).

The possibility of this large stream fed pond or mere is suggested in Steve Boreham’s report cited above and in John Rainer’s report, “Lidgate Castle, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk. Report on Geophysical Survey, September 2018”.

Steve Boreham’s report describes evidence of the diversion of the stream from its natural course across the valley floor into an artificial channel, and the damming of the valley floor with a barrier in the form of a bank or bund, creating a pool, reedbed or marsh. John Rainer’s report also suggests that the geophysical survey area (the meadow immediately south of Lidgate Castle) “may fall within the site of a lost pond which may have extended to the bank to the west. If so, much of the southwestern section of the meadow has been built up from former pond base”. This meadowland abuts the location where the skeletons were found.

Borehole samples taken from this area showed evidence of a wetland habitat, and also evidence of the close proximity of human industrial activity to this area, in the form of iron working, dating from the Iron Age or later (Roman or Medieval). The ferrous nature of the debris evidenced in the samples also explains the large amount of ferrous noise documented in John Rainer’s magnetometer survey. The close proximity of human industrial activity to the place where the skeletons were found adds further context relevant to their discovery.

The LIDAR analysis of the area of the mere shows an artificial channel for the diverted stream cut across the valley floor. The skeletons were found on the edge of this channel. While no further information on the skeletons has been found, despite significant research, their presence in the area of the suggested mere, and more specifically in the bank of the artificial river channel, merits attention and recording in this context. Future discoveries in the area of the proposed mere may be enhanced by knowledge of, or may help explain, their presence here. ”

So, in the end what can we say of our Lidgate skeletons?

Their age is unknown; we don’t know whether the bones were ever radio carbon dated so they could be truly ancient, or could date from the12th or 13th century when Lidgate Castle was inhabited, or from any time up until the 19th century.

Given their discovery in the edge of a watercourse, and the known changes to the watercourses in Lidgate in the past, it is possible that the bones may have been originally buried, or maybe put into a pre-existing pit (thus explaining the upright nature of the finds), in the area below Lidgate Castle and the artificial channel, when cut across the valley floor, impinged upon the burial, possibly disturbing it, but certainly setting up conditions where the flow of water could wash away the bank over time and thus eventually expose the bones.

It is also possible that their place of discovery in 1986 may not have been their original place of interment. The bodies or bones may have been washed away from an original place of deposition upstream and re deposited in the bank of the water channel where further mud and silt washing down could have covered them up.

In both the above cases it is most likely that the bones would have originally had a standard horizontal burial or been put into a-pre existing pit. A vertical grave is so much harder to dig than a traditional one.

If there was a mere in the area the bodies could have been deposited by persons unknown in the marshy water, eventually sinking into the silt and becoming buried there – and there is also the possibility that this could have been a sad case of drowning, accidental or deliberate.

The find spot of the skeletons also lies in land towards the base of the slope leading down from the castle site – again the long term natural or artificial movement and disturbance of soil over time could have lead to movement of the bones, explaining the disturbed nature of the skeletons – and their eventual location.

Unfortunately we don’t know where the bones are now. We do know where they were found however – and in archaeology the context of any find is vital. Their location near the castle, and in a site of possible early medieval landscape and watercourse reorganisation, is of interest. It is hoped that the future planned archaeological investigations near to the site will provide evidence that will help us learn more.

Meanwhile, archaeology increasingly realises the need to be respectful of all human remains, from any date. So, with this in mind, and in addition to our interest in what we can learn from their discovery, we can also acknowledge their humanity. We don’t know who they were; where or when they lived – but we do know that they could have been someone’s mother, father, sister, brother, son or daughter, and though their tale is as yet unknown they can still speak to us across the years.

Chris Michaelides, September 2023